Decolonizing Banania (Part I), the history

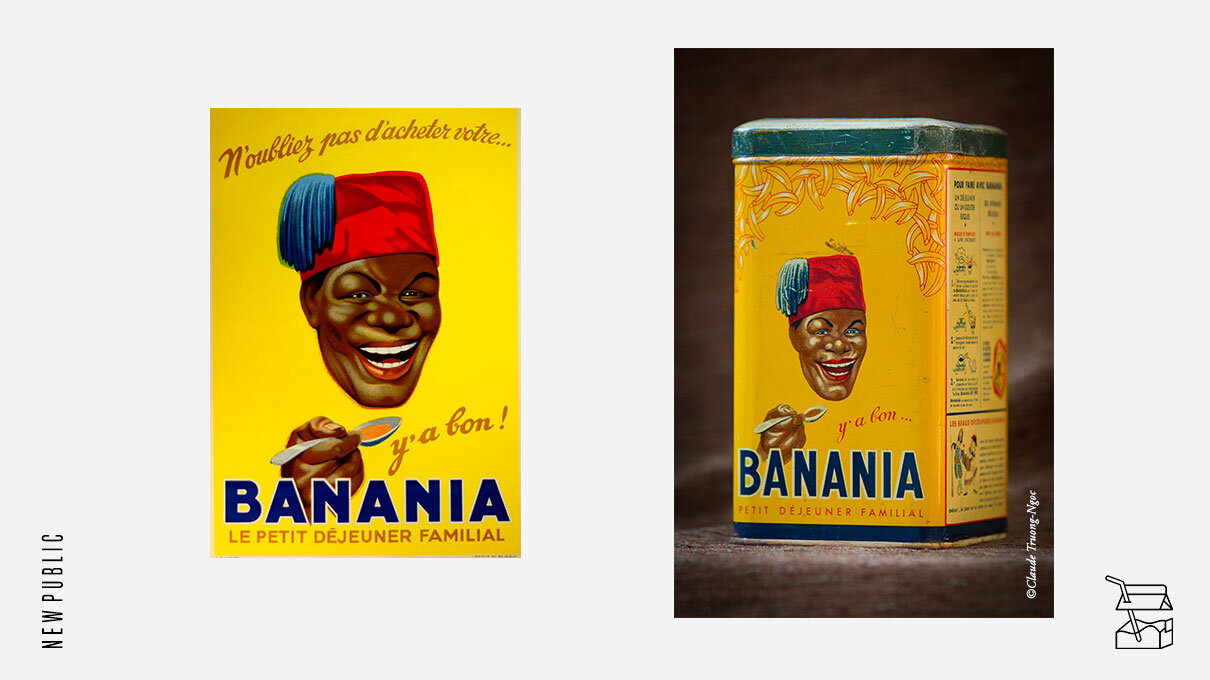

Banania is the name of a very popular chocolate drink mainly commercialized in France. It’s been a part of the French landscape since its creation in 1914 and, for a long time, was the number one selling chocolate milk powder in France. This brand has always been problematic because of its use of the image of a black man as an emblem and a heavy “colonization-was-not-that-bad” type of iconography (and of course the red lips and the big grin and the darker than black skin tone on very white “exotic” attire and… well, you get it).

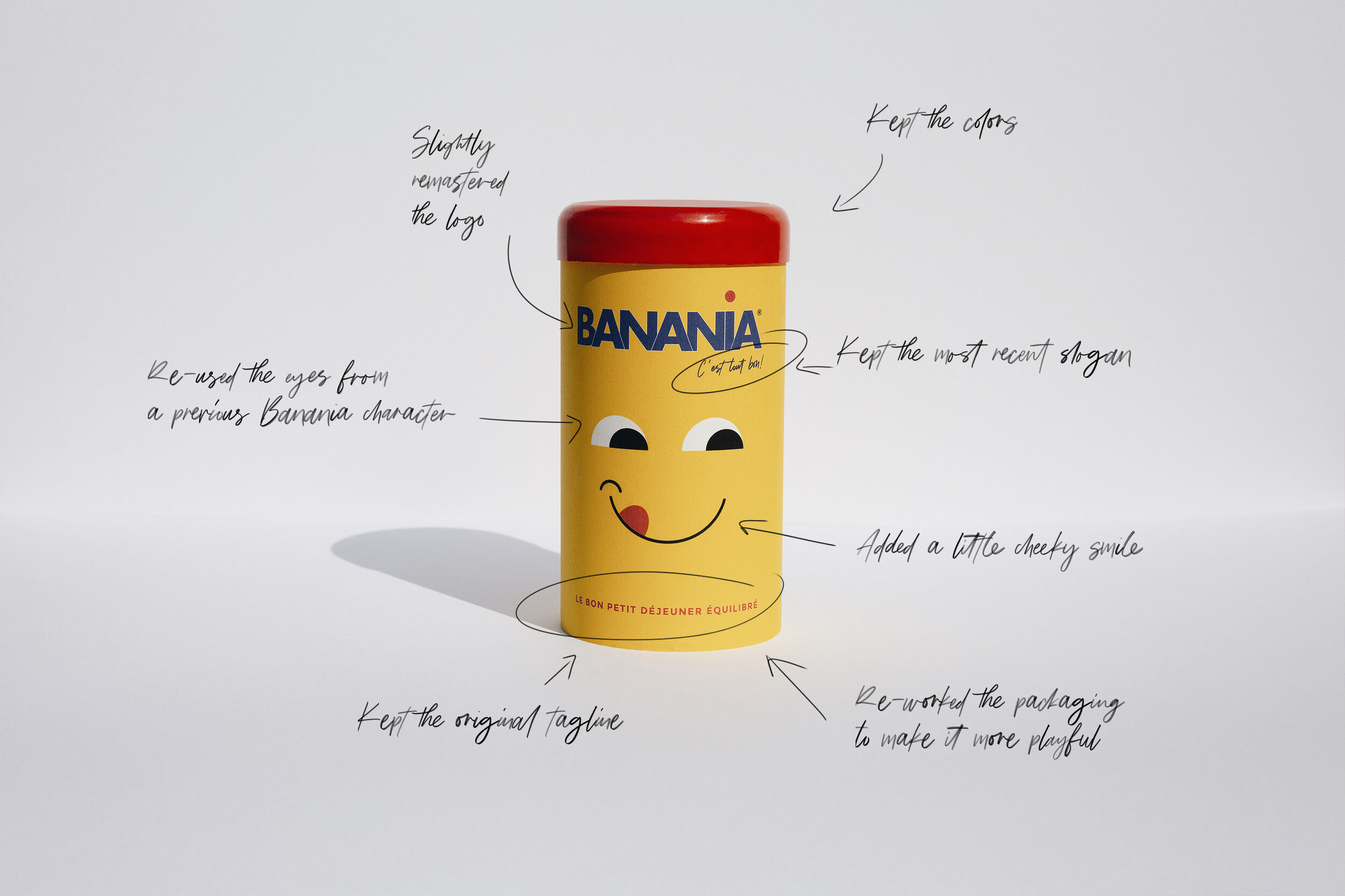

Today, Banania uses the image of a black child in, what I could only define as, a less stereotypical fashion. But, for a brand that has nothing to do with Africa and everything to do with France’s colonial past, it’s still problematic. This is why I decided to try my hand at re-branding it.

I don’t know anyone who works at Banania so to design the new and (hopefully) improved brand identity, I’m going to observe what they do and speculate on what their goals are as a brand. But first, let’s do some research!

I) Banania’s history

The story goes like this. In 1909, the journalist Pierre Lardet goes to Nicaragua where he discovers a “delicious drink made of banana flour, cocoa, crushed grain, and sugar in a village in the heart of the forest.”(1) Back in Paris, he decides to ask for the help of a pharmacist friend to try and replicate the drink. He succeeds and starts commercializing the drink under the name Banania in 1914.

The use of chocolate and banana, two imported products, is quickly associated with the French colonies so it is with no surprise that, from the beginning, the brand decides to use the imagery of an Antillaise (a woman from the French Carribeans). Soon after, the first world war starts to last a little longer than expected and this is when our story really begins. In 1915, Pierre Lardet decides to associate his brand with the war effort and asks Giacomo de Andreis to draw the image of a tirailleur sénégalais (Senegalese rifleman). Lardet’s desire to position his brand as an exotic colonial brand (Banania had a booth at the Colonial Exhibition in Marseille in 1922) and his need to get rid of overflowing stock led him to build a whole campaign around the depiction of a senegalese man enjoying a cup of Banania. This is the second step in the brand’s racist history and the one that’s going to define it to this day.

The image has all the tropes of the racist iconography of the time and it only got worse with time! Then, it got better aaaand it got worse again!

As you can see, in the 1980s, Banania decided to say goodbye to its racist iconography. They traded the image of the senegalese rifleman for the image of a child-like sun. But then, in 1999 they decided to retire the sun and bring back our old friend on the forefront of their packaging.

Then in 2003 they did this:

I wonder what happened between the first and second packaging? Did somebody tell them about the lips among other things and their solution was: “ok let’s reduce the lips then”?

Their idea was to introduce a new character: the senegalese rifleman’s grandson. Needless to say that by that time (2003), people were less than enthusiastic.

Today, they’re still using the image of the grandson and, even though it might look like it’s a little less problematic (aesthetically speaking), it actually still is (very much so if you ask me).

II) Not an African brand

As a kid I always thought Banania was an African brand. I never questioned it one second. I thought it was a drink that came from a sub-saharian country and that the company was from there. I grew up in the 1990s so the first Banania boxes I ever saw were either the ones with the child-like sun or the ones with the original senegalese rifleman.

This is how I remember the brand of my childhood (those elements are probably from way earlier but it’s the memory I have of the brand).

At the time I didn’t know he was supposed to be Senegalese but I did feel like he looked like many people I used to see on a daily basis. I grew up in a very diverse environment with many people from Senegal or Mali so seeing a man that looked like them on a packaging, it was just natural for me to assume it was an African brand. I mean, why would a French brand use the image of a man that was from a country that had nothing to do with their product? (yeah, I know…).

I started realizing that maybe this brand was just using black people and mocking them when, around 2003 (by then I was 15), I came across the packaging I showed you earlier. The one with the huge lips and big grin. This is when I (very unconsciously I must say) stopped seeing Banania as a normal brand and felt uncomfortable whenever I saw one of their products in supermarkets. At the time I didn’t know anything about advertising but I knew this wasn’t right and, frankly, I couldn’t even believe it was legal.

When you look at the evolution of their logo you can see that the brand tried to redeem itself at some point in time. Then, with the trends of vintage logos paired with collective nostalgia in the 2000s, their focus clearly shifted towards riding the trend and using their “mascot” to their advantage. They re-introduced racism in their history.

III) Why re-brand?

From a graphic design/branding point of view, having a mascot is very powerful, especially for a breakfast brand targeting children. Think Tony the Tiger or Ronald McDonald. So I understand that they tried to re-create the success of the early days. However, they were fully aware that their logo was considered racist and humiliating by many. For years, there were complaints and people were vocal about it (they were even sued for their problematic slogan and had to change it).

I do not exactly understand the mechanics behind the reasons why, for over a hundred years, a brand would consistently decide to be on the side of racism. It fuels negative brand awereness and will never cease to do so. The fight against racism is only going forward, there’s no going back to when this was acceptable. On a human level, it reflects very poorly on the people running Banania but it also just doesn’t look like a viable brand strategy in the long run.

Now, that being said, the company was created over 100 years ago and is still here so it means people like their products - and are either unaware of the backstory or they like it so much they look past it. Personally, I remember the chocolate milk to be very good and it’s a brand that is part of my childhood so I have some attachment to it. Would I buy it nowadays? Certainly not. Would I buy it if they made a conscious and visible effort to get rid of their colonial past and racist imagery? Maybe, yes.

Brands, like people, can redeem themselves in my book. I think it’s easier for Banania to rely on images that have proven to work. Selling a product is hard, especially when one of your main competitors is Nestlé. But racism is unacceptable; especially when you’re trying to make money thanks to it.

This is why I decided to try to re-brand Banania. Not because I hate it but because I actually like the idea of what it could be. Brands are part of our lives whether we like it or not. This one happens to be part of my childhood and I would love to see it being on the good side of history for a change.

You can check out the re-design here.

(1) Banania

Decolonizing Banania (Part II)

Check out my Banania re-design by clicking on the link below.